The Art of the Tyrol…

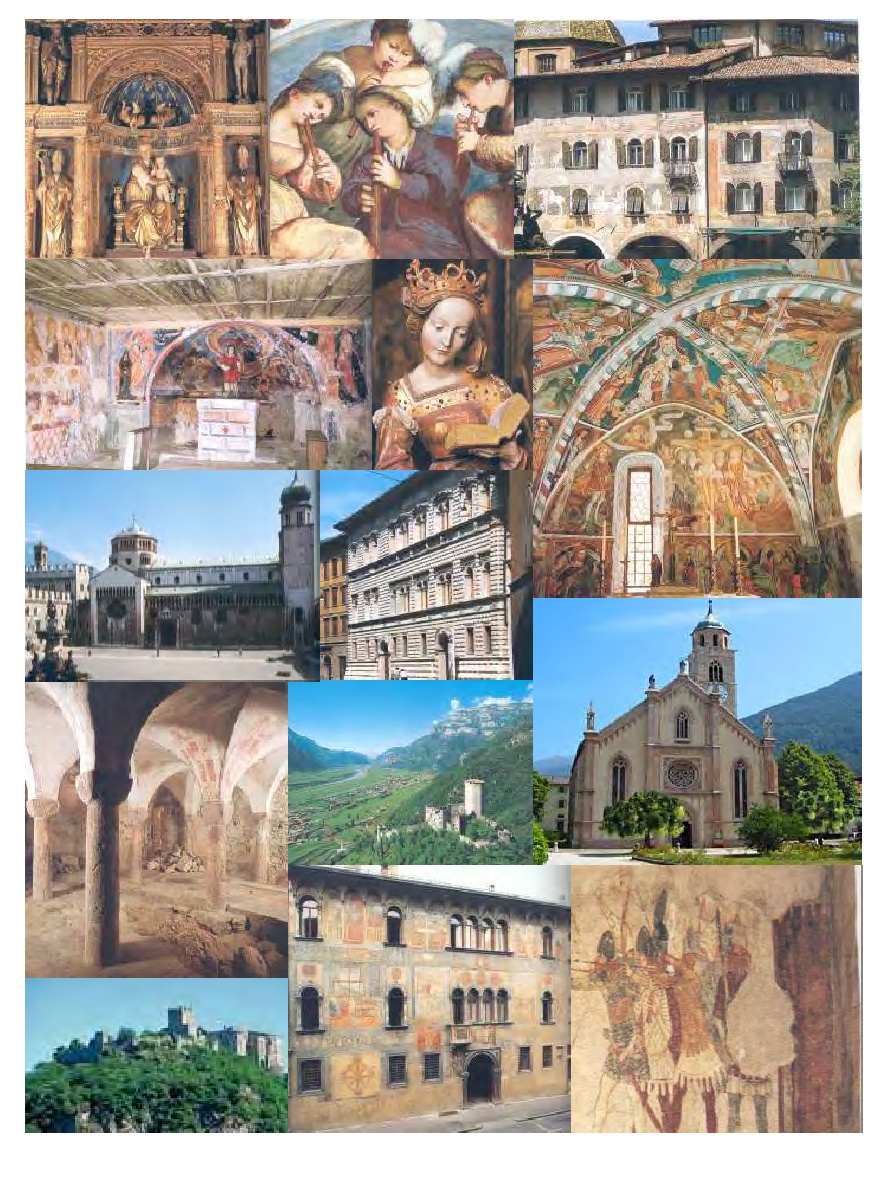

ely shrines, capitelli, or a crucifix. Looking up the mountainsides, they beheld ancient castles replete with art from a variety of artists, castles where feudal lords meted out justice and exacted tithes on behalf of a higher authority. The Trentino countryside is marked by architectural works complete with sculptures and paintings by skillful artists. When the town dwellers moved about their cities and towns, when the people from the countryside came to these towns for services or to transact their affairs, they passed edifices and monuments that boasted of charming art and sculpture and communicated a sense of continuity and harmony. Poor as they were, they had the riches of so much art in their ordinary and everyday environments…

ely shrines, capitelli, or a crucifix. Looking up the mountainsides, they beheld ancient castles replete with art from a variety of artists, castles where feudal lords meted out justice and exacted tithes on behalf of a higher authority. The Trentino countryside is marked by architectural works complete with sculptures and paintings by skillful artists. When the town dwellers moved about their cities and towns, when the people from the countryside came to these towns for services or to transact their affairs, they passed edifices and monuments that boasted of charming art and sculpture and communicated a sense of continuity and harmony. Poor as they were, they had the riches of so much art in their ordinary and everyday environments…

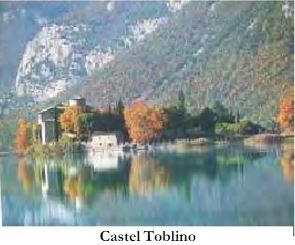

The art of the Trentino or the Tyrol was profoundly influenced by its history and geography. It lies at the extreme southern edge of the Germanic empire,the Tyrol or the Welsch Tirol so that it became a meeting place and a sponge between the Nordic and the Latin cultures. While flanked by the Lombardy and the Veneto, the Trentino or the Sud Tirol was never part of Italy until 1919. For 800 years it was an empire or lands under the control of feudal bishops many Germanic and then for the 200 years prior to its annexation to Italy, it was the part of the Austrian Hungarian Empire. This cultural and geographic combination makes its artistic expressions heterogeneous and fascinating. This very geography and cultural mixture prompted St Charles Borromeo to select the Tyrol as the logical and ideal location for the Ecumenical Council of Trent which launched the Counter Reformation that fueled the assertiveness of the Baroque.

The art of the Trentino or the Tyrol was profoundly influenced by its history and geography. It lies at the extreme southern edge of the Germanic empire,the Tyrol or the Welsch Tirol so that it became a meeting place and a sponge between the Nordic and the Latin cultures. While flanked by the Lombardy and the Veneto, the Trentino or the Sud Tirol was never part of Italy until 1919. For 800 years it was an empire or lands under the control of feudal bishops many Germanic and then for the 200 years prior to its annexation to Italy, it was the part of the Austrian Hungarian Empire. This cultural and geographic combination makes its artistic expressions heterogeneous and fascinating. This very geography and cultural mixture prompted St Charles Borromeo to select the Tyrol as the logical and ideal location for the Ecumenical Council of Trent which launched the Counter Reformation that fueled the assertiveness of the Baroque.

These remarks are an introduction to how we will present in future editions of the multi-faceted aspects of the art of the Trentino from its frescoed palaces, its cathedrals and churches from different eras, its village churches and shrines to its castles with its sculptures and paintings. We will attempt to move around the Trentino to highlight and explain the history and the features of these expressions. We welcome your inquiries and/or suggestions regarding specific examples of the art. Just below, we present the church of San Virgilio in the shadow of the Brenta Dolomites. The church is illustrated by the famous Simone Baschenis.

]

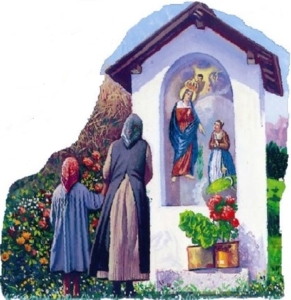

]

Caputei – Tyrolean Shrines

There are many art treasures scattered around the Tyrol. They can be found in churches, castles and the frescoed palaces in its cities. They were commissioned by the institutional church, by prince bishops , and by wealthy patrons. But throughout the entire Tyrol, there is another form of art neither inspired nor sponsored by the Church or the powerful. This is the devotional art form of the Capitelli, I Caputei in dialect, wayside shrines that can be found at the outskirts and the crossroads of towns and villages and on the foot hills of the mountains. They are the products of the local popular piety of the peasants, the contadini, built with humble means by people of yet humbler means. A capitello or a “caputel” is a mini-chapel, usually sitting on a square foundation with acharacteristic mini roof. They are also found in a similar form but embedded in walls in the villages. Under the cover of this mini roof, there is a niche where there is situated a statue, a cross, a painting, a fresco reflecting local piety or devotions. The images might include a crucifix, the Virgin Mary, St Joseph, a variety of saints. St Antony, the Abbot, is often found since he was the patron of animals, a precious commodity for the contadini, the farmers.Flowers and votive candles are often found in front of the images. In the absence of street or road signs, they had a practical purpose and were markers for travelers. They were found along the ancient roads of the countryside, in places most exposed to dangers like bridges, gorges, mountain slopes, where one felt yet a greater need for divine protection…they are there to attest to the precarious state of the farmer’s existence and the need to dialogue with the sacred.

There are many art treasures scattered around the Tyrol. They can be found in churches, castles and the frescoed palaces in its cities. They were commissioned by the institutional church, by prince bishops , and by wealthy patrons. But throughout the entire Tyrol, there is another form of art neither inspired nor sponsored by the Church or the powerful. This is the devotional art form of the Capitelli, I Caputei in dialect, wayside shrines that can be found at the outskirts and the crossroads of towns and villages and on the foot hills of the mountains. They are the products of the local popular piety of the peasants, the contadini, built with humble means by people of yet humbler means. A capitello or a “caputel” is a mini-chapel, usually sitting on a square foundation with acharacteristic mini roof. They are also found in a similar form but embedded in walls in the villages. Under the cover of this mini roof, there is a niche where there is situated a statue, a cross, a painting, a fresco reflecting local piety or devotions. The images might include a crucifix, the Virgin Mary, St Joseph, a variety of saints. St Antony, the Abbot, is often found since he was the patron of animals, a precious commodity for the contadini, the farmers.Flowers and votive candles are often found in front of the images. In the absence of street or road signs, they had a practical purpose and were markers for travelers. They were found along the ancient roads of the countryside, in places most exposed to dangers like bridges, gorges, mountain slopes, where one felt yet a greater need for divine protection…they are there to attest to the precarious state of the farmer’s existence and the need to dialogue with the sacred.

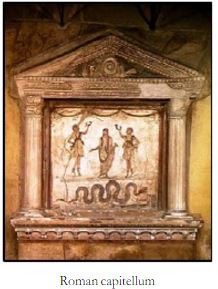

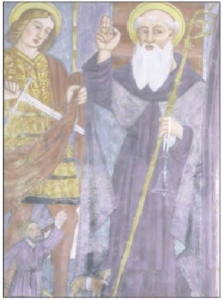

While spontaneously built by the local people over the years, they have a specific and historic origin and precedent that reflects on the history of the Tyrol. The Tyrol was an area populated by peoples and tribes that practiced their own religious expressions or what could be called pagan. For a while, Rome had conquered the Tyrol, conferred Roman citizenship on the peoples and left behind its own brand of pantheistic practices. Rome’s believed in many deities and these deities abided everywhere including the woods and their fields…and even their homes. They had shrines to these deities in their homes, at the crossroads of their roads and in their fields. They were means to derive blessings and presence in their homes, environments and fields. They were called compitelum where the name and form of the capitelli derive. They were “little temples” where one`s devotion to the deities could be expressed. To understand this history, Christianity first came to the Tyrol in the person of St Virgilius, IV Century, who began the process of transitioning the peoples to this “new” faith. This process continued slowly for several centuries so that “pagan” practices also became “converted” and transformed into Christian expressions. Hence,the Roman shrines became the capitelli.“The story of the capitelli is a humble story which evokes the past and popular piety, the world of the contadino and his daily work in the fields in synch with the cycles of the seasons, a natural religiosity of these mountain people that included simple gestures and a spontaneous piety. It evokes images of morning processions at springtime, of people kneeling to invoke protections for their harvests or relief in the moments of calamity…of wayfarers with their hat in hand to rest after walking a great distance, of elders bent over stopping to say a prayer, of women gathered to recite the rosary.” Severino Riccadonna: Capitelli.

these deities abided everywhere including the woods and their fields…and even their homes. They had shrines to these deities in their homes, at the crossroads of their roads and in their fields. They were means to derive blessings and presence in their homes, environments and fields. They were called compitelum where the name and form of the capitelli derive. They were “little temples” where one`s devotion to the deities could be expressed. To understand this history, Christianity first came to the Tyrol in the person of St Virgilius, IV Century, who began the process of transitioning the peoples to this “new” faith. This process continued slowly for several centuries so that “pagan” practices also became “converted” and transformed into Christian expressions. Hence,the Roman shrines became the capitelli.“The story of the capitelli is a humble story which evokes the past and popular piety, the world of the contadino and his daily work in the fields in synch with the cycles of the seasons, a natural religiosity of these mountain people that included simple gestures and a spontaneous piety. It evokes images of morning processions at springtime, of people kneeling to invoke protections for their harvests or relief in the moments of calamity…of wayfarers with their hat in hand to rest after walking a great distance, of elders bent over stopping to say a prayer, of women gathered to recite the rosary.” Severino Riccadonna: Capitelli.

Ex Voto: Faith Expressed in Art

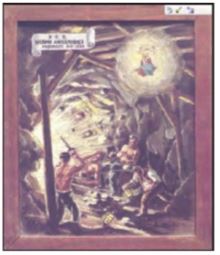

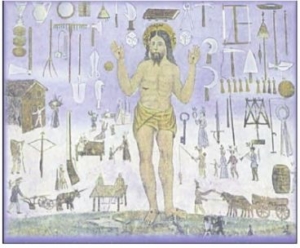

The Trentino has a special expression of our people’s faith expressed artistically on votive tablets, the Ex Voto. An ex-voto is a votive offering to a saint or to God. It is given in fulfillment of a vow (hence the Latin term, short for ex voto suscepto, “from the vow made”) or in gratitude or devotion. Ex-votos are placed in a church or chapel where the worshiper seeks grace or wishes to give thanks. When an illness seemed notto have a remedy or recourse, when the “medicine” was a science simply not available,the unfortunates, those who were ill would make a covenant with the divinity. The Ex Voto tablet was a testimonial of a supernatural intervention in the face of ever present dangers and death itself. These tablets or framed pictures depict scenes painted in oils or tempera or drawn in pencil commemorating grace received in cases of illness, accident or danger giving evidence of their piety and devotion. They were commissioned by individuals or even communities from mostly unknown painters to record a “miracle” of which they had been the protagonist and beneficiaries. They hang on the walls of sanctuaries and side altars communicating the popular devotion or religious faith of our villages, the gratitude expressed by simple people to the saints or to those persons to whom they turned in times of needs. These Ex Voto tablets have their expressive expositions in some of the major sanctuaries of devotion in the Tyrol. They include Montagnaga di Pine` (see article on page 29) S.Romedio, S. Valentino of Ala, S. Croce di Bleggio, the Madonna del Monte in Rovereto, l`Addolorata a Cavalese, the Madonna dell`Aiuto a Fiera di Primiero, the chapel of S. Antonio in Albiano; the Madonna of the Baselga of Bresimo, S. Vigilio of Tione…to name but a few. These objects are considered “humble” art yet they served as expressive symbols, megaphones announcing and proclaiming a special and blessed happening. It is within this world of legend, of piety and faith that ex votos recou

The Trentino has a special expression of our people’s faith expressed artistically on votive tablets, the Ex Voto. An ex-voto is a votive offering to a saint or to God. It is given in fulfillment of a vow (hence the Latin term, short for ex voto suscepto, “from the vow made”) or in gratitude or devotion. Ex-votos are placed in a church or chapel where the worshiper seeks grace or wishes to give thanks. When an illness seemed notto have a remedy or recourse, when the “medicine” was a science simply not available,the unfortunates, those who were ill would make a covenant with the divinity. The Ex Voto tablet was a testimonial of a supernatural intervention in the face of ever present dangers and death itself. These tablets or framed pictures depict scenes painted in oils or tempera or drawn in pencil commemorating grace received in cases of illness, accident or danger giving evidence of their piety and devotion. They were commissioned by individuals or even communities from mostly unknown painters to record a “miracle” of which they had been the protagonist and beneficiaries. They hang on the walls of sanctuaries and side altars communicating the popular devotion or religious faith of our villages, the gratitude expressed by simple people to the saints or to those persons to whom they turned in times of needs. These Ex Voto tablets have their expressive expositions in some of the major sanctuaries of devotion in the Tyrol. They include Montagnaga di Pine` (see article on page 29) S.Romedio, S. Valentino of Ala, S. Croce di Bleggio, the Madonna del Monte in Rovereto, l`Addolorata a Cavalese, the Madonna dell`Aiuto a Fiera di Primiero, the chapel of S. Antonio in Albiano; the Madonna of the Baselga of Bresimo, S. Vigilio of Tione…to name but a few. These objects are considered “humble” art yet they served as expressive symbols, megaphones announcing and proclaiming a special and blessed happening. It is within this world of legend, of piety and faith that ex votos recou nt the stories of common folk. The creators of these pictures never claimed to have created works of art but they are strikingly beautiful as well as being a precious testimony of the everyday life a bygone age.

nt the stories of common folk. The creators of these pictures never claimed to have created works of art but they are strikingly beautiful as well as being a precious testimony of the everyday life a bygone age.

In 1981 in Trento, there was an exhibition and a survey of the ex voto tablets that had been produced between 16th to the 19th century. There were approximately 1000 ex voto objects. In the parish church of S. Anna at Montagnagadi Pine`, 400 ex voto tablets were destroyed due to the negligence of the parish priest that had situated candles under the tablets. In the Valsugana, the ex votos were gathered in chapels in the country side where there had resided hermits. When the hermits had to leave these places by degree of the Emperor Joseph II of Vienna at the end of the 18th century, the more “precious” objects were stolen by thieves. This happened in all too many places. In summary, these historic tablets document a world of customs that has now disappeared but provide a glimpse of the historic and traditional religiosity of our people.

Alberto Folgheraiter — author of I Sentieri dell`Infinito-Storia dei Santuari del Trentino-Alto Adige

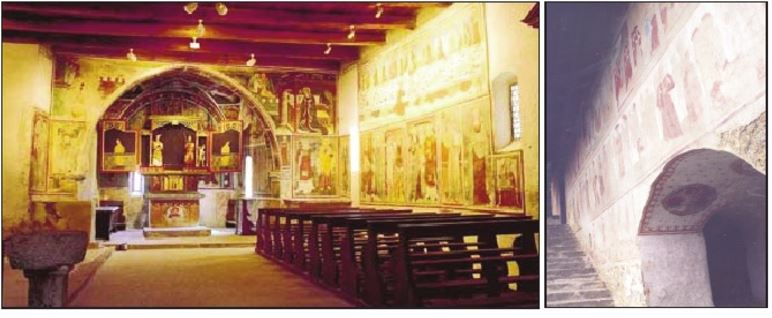

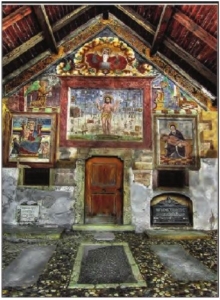

The Rendena’s Jewel: San Stefano

Dominating the Rendena Valley is the lovely village of Carisolo where history, legend and art all combine to enhance its significance. Dominating Carisolo on a high granite promontory is the historic cemetery church of San Stefano erected in 1100 extended and decorated in the following centuries. It stands as the gateway to the Val di Genova and the Natural Park of the Adamello Brenta. Once possibly a prehistoric fortress, records refer to it as early as 1214. No less than the great Charlemagne is said to have stopped and passed its very location. The legend narrates how he saw the church isolated on a rock, went to it and left a document regarding his exploits. This episode is part of the cultural and the oral tradition of the Rendena people but is in evidence in the magnificent fresco in the church along with its expressive legend underneath the images confirming this history or reinforcing the legend. San Stefano is a magnificent art treasure; the jewel of the entire valley. Its ancient interior and exterior walls are bedecked with contributions of a variety of artists, but in particular, its walls were the canvases of the Baschenis, a 200-year dynasty of itinerant painters, who left their work throughout the Trentino. The Baschenis were able to establish themselves as the painters of the labors and sufferings of the people of mountain farmer. San Stefano has a magnificent display of their frescoes both in the interior and on the exterior walls.

Dominating the Rendena Valley is the lovely village of Carisolo where history, legend and art all combine to enhance its significance. Dominating Carisolo on a high granite promontory is the historic cemetery church of San Stefano erected in 1100 extended and decorated in the following centuries. It stands as the gateway to the Val di Genova and the Natural Park of the Adamello Brenta. Once possibly a prehistoric fortress, records refer to it as early as 1214. No less than the great Charlemagne is said to have stopped and passed its very location. The legend narrates how he saw the church isolated on a rock, went to it and left a document regarding his exploits. This episode is part of the cultural and the oral tradition of the Rendena people but is in evidence in the magnificent fresco in the church along with its expressive legend underneath the images confirming this history or reinforcing the legend. San Stefano is a magnificent art treasure; the jewel of the entire valley. Its ancient interior and exterior walls are bedecked with contributions of a variety of artists, but in particular, its walls were the canvases of the Baschenis, a 200-year dynasty of itinerant painters, who left their work throughout the Trentino. The Baschenis were able to establish themselves as the painters of the labors and sufferings of the people of mountain farmer. San Stefano has a magnificent display of their frescoes both in the interior and on the exterior walls.

Charlemagne

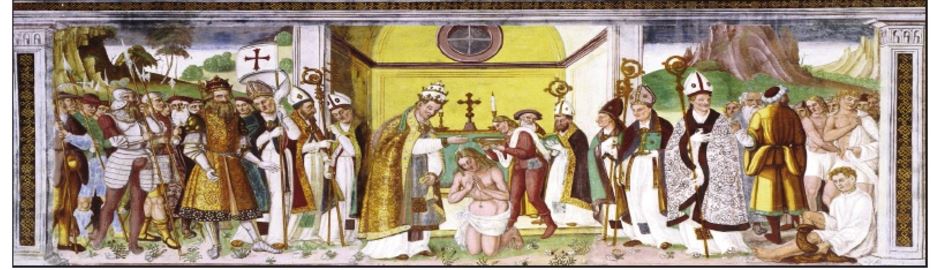

The large fresco which can be seen on the inside northeast façade tells of the legendary expedition of Charlemagne through Val Camonica, Val di Sole and Val Rendena. The landscape of these valleys forms a background to the scene in which the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, surrounded by his retinue attends the baptism of a catechumen. This baptism is administered by the Pope in the presbytery of a chapel. In this fresco, Simone II Baschenis, recounts a Medieval legend in Renaissance style. Thanks to the bright colors and lush decorations of the garments, the painter conserves the legendary dimension of the story. Under the fresco there is a long inscription in the vernacular,explaining the painting. The text known today as “The Privilege of St. Stephen’s in Rendena recounts the story of the passing of Charlemagne in the area.

The large fresco which can be seen on the inside northeast façade tells of the legendary expedition of Charlemagne through Val Camonica, Val di Sole and Val Rendena. The landscape of these valleys forms a background to the scene in which the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, surrounded by his retinue attends the baptism of a catechumen. This baptism is administered by the Pope in the presbytery of a chapel. In this fresco, Simone II Baschenis, recounts a Medieval legend in Renaissance style. Thanks to the bright colors and lush decorations of the garments, the painter conserves the legendary dimension of the story. Under the fresco there is a long inscription in the vernacular,explaining the painting. The text known today as “The Privilege of St. Stephen’s in Rendena recounts the story of the passing of Charlemagne in the area.

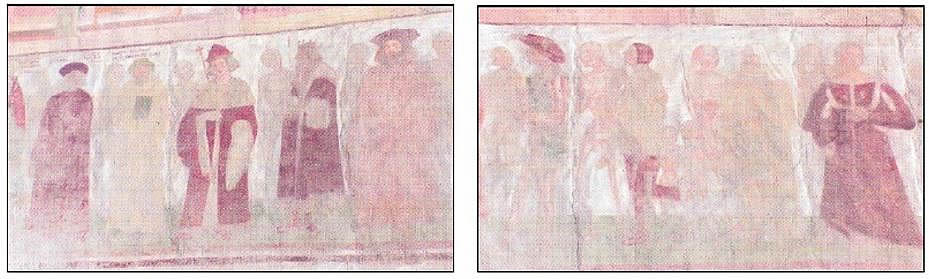

The Dance of Death

The splendid fresco of the Dance of Death can be found on the external south-west façade. It is a late medieval iconographical theme which shows humans and skeletons dancing together. The skeletons are a personification of death, whereas the humans are usually dressed in the representative clothes of the various social categories of the time, from the most powerful like the Pope and Emperor, prelates, princes and noblemen, to the most humble, like the middle classes and peasants. The fresco was painted in 1519 by Simone II Baschenis, one of the most talented 16th century artists, who belonged to the famous dynasty of Bergamo painters, the Baschenis family. This work communicates the inevitability and impartiality of death which strikes everyone without distinction, churchmen and laymen, rich and poor, young and old. The images evoke fear in observers and seem to exhort them to think in time about saving their souls. The inside of the church has a series of fascinating 16th century frescoes of great beauty.

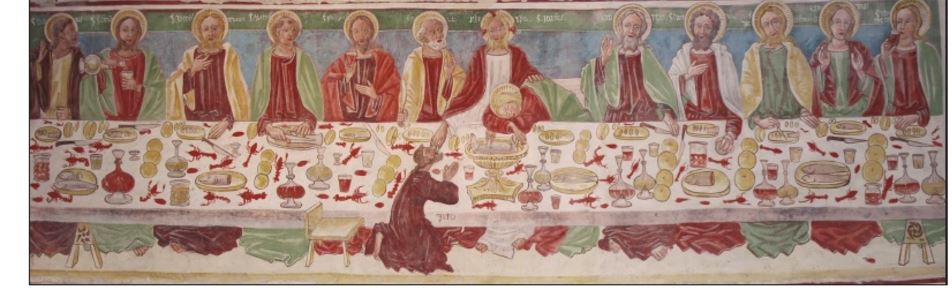

The Last Supper

The upper internal south-west façade of the church is covered with a fresco depicting the Last Supper. This famous scene is frescoed with spontaneity and immediacy despite the rudimentary prospective, typical of the Baschenis. The twelve apostles are looking towards the viewer and are seated with Jesus at a Renaissance table, covered with a white cloth. The table is lavishly set with an abundance of earthenware and food. The lamb, the symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, is

table, covered with a white cloth. The table is lavishly set with an abundance of earthenware and food. The lamb, the symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, is

served on an imposing gilded dish. The plates are filled with fish and on the tablecloth there is abundant bread with bottles of wine and different types of glassware. The many red prawns spread over the table give the banquet a note of color and are a constant in the Last Suppers painted in the church found in the Alps. The artists painted the shellfish to create a direct contact with the people. In fact in the past the prawn abounded in the Trentino rivers and was an integral part of the diet at that time. This animal also lends itself to a symbolic reading. It can thus be seen as a reference to resurrection and the human soul, which returns to life after death. The color of the prawn, which turns from grey to red after cooking, also alludes to the Passion. The church is now used for special celebrations such as art exhibits and concerts.

Art of the Maddalene Mountains

While there might not be art museums and art conservations, the people of the mountain areas and valleys confronted art in their churches, castles, mansions of the nobility and in the way side shrines.

While there might not be art museums and art conservations, the people of the mountain areas and valleys confronted art in their churches, castles, mansions of the nobility and in the way side shrines.

Cis, Livo and Rumo are the small villages that lie at the bottom of the Maddalene in the municipalities of Bresimo. They retain a wealth of ecclesiastical and civil properties, witnesses of a past of faith and history. Over the centuries, various noble dynasties ruled this territory, leaving behind castles and stately homes, still the parTly visible signs of their presence. The Christian faith anddevotion of the local populations is clearly witnessed by churches, votive chapels and sacred murals scattered all villages, even the smallest shrines  along the country roads and mountains.

along the country roads and mountains.

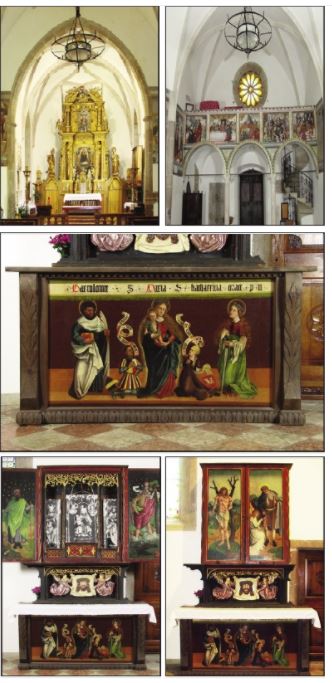

Above the village of Bresimo at 1280 meters above sea level, there are the ruins of the castle of Altaguarda, the residence of local aristocratic families and for many years, the residence of the members of the powerful family of Thun. It was attacked and burned during the peasant in 1407. It was later rebuilt by Baldassare Thun, who lived there with his wife Philippa of Arco. At the end of 1800 it was purchased by the City of Bresimo and now it is site for visitors who want to enjoy the marvelous view of the valley below. The population of Baselga di Bresimo is the beautiful church of Santa Maria Assunta, invoked and venerated in the past centuries by the local people during the severe drought that affected the countryside and still known as the “Madonna of the Water.” One hears of it from 1324 and its history is closely linked with the nobility of the castle above. It was enlarged in 1335 with the support of the lords of Altaguarda. In its interior, there is a excellent altar with panel doors. It was donated by Be nardino Thun and Bridget of Arsio. Worthy of note are the frescoes in the nave that are inspired by the “Small Passion”of the sixteenth-century German engraver Albrecht Durer and a stone  tabernacle of the Gothic style.

tabernacle of the Gothic style.

On the hill east of the village of Cish, there is the churchof St. George built in its current form in 1594. Insidehile there might not be art museums and there is a Via Crucis (Stations of the Cross) of the eighteenth century and a large fresco of the Crucifixion. The main altar is of the seventeenth century, while the two side altars are in neoclassical style.

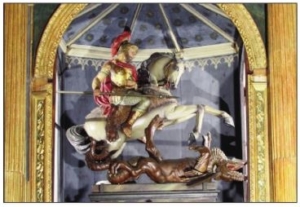

Of special Interest is the statue of St. George slaying the dragon, the work of Ferdinand Demetz of the ValGardena, donated to the church in 1891 by emigrants of Cis employed as miners in Colorado.

In the  municipality of Livo there are four churches, one for each section of the town. The oldest and most valuable is the church of the Nativity of Mary in Varollo, the parish church of area.. Positioned on a hill straddling the Val di Non and Val di Sole, it was rebuilt in 1537. The façade dominates the impressive fresco of St.Christopher and on the north side stands a beautiful loggia called “glesiot.”(little church). Inside, there is the noteworthy trio of gilded wooden altars, the work of local carvers of 1600. There is also a pulpit of the 1700 painted wood to simulate marble. The altar piece of theNativity of Mary, in the center of the main altar, is the work of the painter of Brescia Carlo Pozzi made in 1669. Several frescoes from different eras adorn the walls and the patron saint of the church. There are very ancient churches full of frescoes, the churches of St. Martin in Livo and St. Anthony Abbot in Preghena.

municipality of Livo there are four churches, one for each section of the town. The oldest and most valuable is the church of the Nativity of Mary in Varollo, the parish church of area.. Positioned on a hill straddling the Val di Non and Val di Sole, it was rebuilt in 1537. The façade dominates the impressive fresco of St.Christopher and on the north side stands a beautiful loggia called “glesiot.”(little church). Inside, there is the noteworthy trio of gilded wooden altars, the work of local carvers of 1600. There is also a pulpit of the 1700 painted wood to simulate marble. The altar piece of theNativity of Mary, in the center of the main altar, is the work of the painter of Brescia Carlo Pozzi made in 1669. Several frescoes from different eras adorn the walls and the patron saint of the church. There are very ancient churches full of frescoes, the churches of St. Martin in Livo and St. Anthony Abbot in Preghena.

In the center of Livio, there stands the palace ALIPRANDINI Laifenthurn, home to ancient noble families of the area. It was recently restored by the Municipality of Livio. There are many historic houses are scattered in each of the

Written by Gianantonio Agosti, President — Anastasia Val di Non — Associazione delle Guide aiBeni Sacri

The Art of the Val di Fiemme

The Val di Fiemme has always been a veritable crosswords for different cultures each of which left behind distinctive and varied artistic expressions. One finds art from the Veneto, Lombardy, Germany, South-Tyrol and Ladin lands. In the villages of Tesero, Cavalese and Predazzo, one finds frescos and paintings from these very areas along with German-style Gothic churches, palaces inspired by the Italian Renaissance and Baroque altars created by Ladin artists. In Tesero, there is the Roman bridge considered the most important architectural piece of art of the Middle Age in Fiemme. There are elegant fifteenth century-style bell towers are San Leonardo in Tesero and Varena’s. The end of the fifteenth century and at the beginning of sixteenth century there occurs the remodeling of church Sant’ Eliseo in Tesero and of the Bishop’s Palace: the palace of the Grand Community of Fiemme in Cavalese. The palace, with its Renaissance and Gothic era is the best known example of the“Clesian” art of Trentino that reflects the governance of the Prince Bishop Bernardo Clesio (1514-1539). The valley’s most ancient paintings are on the façade of Casa Cazzana (also called Casa Riccabona) in Cavalese (XIV). The local painting prospered in the Seventeenth century, when they frescoed some of the churches of Fiemme. Orazio Giovannelli (1588-1639) is the leading figure of the “School of Art of Fiemme”, the only one in Trentino. Giovannelli was born in Tesero and studied in Venice. His works of art bring the Mannerism of Venetoto the mountains of Trentino, in particular into the creation of the altar piece in Valfloriana. Also Francesco Furlaner was from Tesero: he painted the altar piece in the parish church of Panchià (1677-1719). The 17-century most important artist is Giuseppe Alberti from Tesero (1540-1716), architect and painter. But the most relevant century for the painting in Fiemmeis the Eighteenth, when the Unterperger’s

The Val di Fiemme has always been a veritable crosswords for different cultures each of which left behind distinctive and varied artistic expressions. One finds art from the Veneto, Lombardy, Germany, South-Tyrol and Ladin lands. In the villages of Tesero, Cavalese and Predazzo, one finds frescos and paintings from these very areas along with German-style Gothic churches, palaces inspired by the Italian Renaissance and Baroque altars created by Ladin artists. In Tesero, there is the Roman bridge considered the most important architectural piece of art of the Middle Age in Fiemme. There are elegant fifteenth century-style bell towers are San Leonardo in Tesero and Varena’s. The end of the fifteenth century and at the beginning of sixteenth century there occurs the remodeling of church Sant’ Eliseo in Tesero and of the Bishop’s Palace: the palace of the Grand Community of Fiemme in Cavalese. The palace, with its Renaissance and Gothic era is the best known example of the“Clesian” art of Trentino that reflects the governance of the Prince Bishop Bernardo Clesio (1514-1539). The valley’s most ancient paintings are on the façade of Casa Cazzana (also called Casa Riccabona) in Cavalese (XIV). The local painting prospered in the Seventeenth century, when they frescoed some of the churches of Fiemme. Orazio Giovannelli (1588-1639) is the leading figure of the “School of Art of Fiemme”, the only one in Trentino. Giovannelli was born in Tesero and studied in Venice. His works of art bring the Mannerism of Venetoto the mountains of Trentino, in particular into the creation of the altar piece in Valfloriana. Also Francesco Furlaner was from Tesero: he painted the altar piece in the parish church of Panchià (1677-1719). The 17-century most important artist is Giuseppe Alberti from Tesero (1540-1716), architect and painter. But the most relevant century for the painting in Fiemmeis the Eighteenth, when the Unterperger’s  dynasty became masters of Trentino’s Baroque art. The forefather Michelangelo Unterperger (1695-1758), who studied in Venice, became the dean of the Academy of Vienna,but in his valley he left important masterpieces like The Guardian Angel in the church of Stramentizzo, nowadays arranged in the Parish of Molina di Fiemme. Francesco Sebaldo Unterperger’s pieces of art (1706-1776), Michelangelo’s brother, can be watched in Molina di Fiemme and in the churches of Tesero.

dynasty became masters of Trentino’s Baroque art. The forefather Michelangelo Unterperger (1695-1758), who studied in Venice, became the dean of the Academy of Vienna,but in his valley he left important masterpieces like The Guardian Angel in the church of Stramentizzo, nowadays arranged in the Parish of Molina di Fiemme. Francesco Sebaldo Unterperger’s pieces of art (1706-1776), Michelangelo’s brother, can be watched in Molina di Fiemme and in the churches of Tesero.

Afterwards, Cristoforo Unterperger (1732-1798) distinguished himself. He studied with Francesco Sebaldo and Michelangelo and moved to Vienna and to Rome. Two of his masterpieces are the altar piece of San Giorgio in the parish church of Predazzo and the oval canvas of Assunta of the church in Parco della Pieve of Cavalese. Unterperger’s pupil was Antonio Longo (1748-1820), priest, painter and architect of Varena, author of his house’s fresco in Varena and of numerous Crucified Christ and paintings. The protagonists of Fiemme’s painting in the Nineteenth century were Francesco Antonio (1754-1836), Antonio(1792-1855) and Carlo Vanzo (1824-1893). The painter from Predazzo, Bartolomeo Rasmo (1810-1846), was inspired by Tintoretto. He painted the Last Dinner of the parish church of Ziano.

The Palace

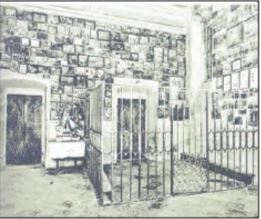

The ancient headquarters of the Magnifica Comunità diFiemme, with its Art Gallery Museum and the historical archive, nowadays is one of the most active and elegant museums. The palace represents – considering what is contained in it, its history, its tradition, its marked identity handed down to the local people – the natural space, the elected place where man can carry on composing a long story of amazing civil and human meaning. The excellent seven-year-long restoration, finished in 2012, has given back to citizens of Val di Fiemme an extraordinary and wonderful temple of culture. Guided and theatrical visits reveal all the secrets that are still hidden in the palace’s ancient walls. After the renovation, the visitor can also explore the jails of the nineteenth century where he can see the suggestive etchings that can tell life, memories and sentences of the people imprisoned there. A discreet lighting instills to the museum and to its art gallery a mysterious atmosphere: hither and thither it casts surprising lighted layouts that bring out the beauty of paintings and frescos. The 150 masterpieces of the School of Art of Fiemme (made by Michelangelo, Cristoforo and Francesco Sebaldo Unterperger) hung on the walls showing their renewed charm. Some canvas are so well-lighted to let the visitor penetrate the space and approach the subject, as if they would tell him something secret.

The ancient headquarters of the Magnifica Comunità diFiemme, with its Art Gallery Museum and the historical archive, nowadays is one of the most active and elegant museums. The palace represents – considering what is contained in it, its history, its tradition, its marked identity handed down to the local people – the natural space, the elected place where man can carry on composing a long story of amazing civil and human meaning. The excellent seven-year-long restoration, finished in 2012, has given back to citizens of Val di Fiemme an extraordinary and wonderful temple of culture. Guided and theatrical visits reveal all the secrets that are still hidden in the palace’s ancient walls. After the renovation, the visitor can also explore the jails of the nineteenth century where he can see the suggestive etchings that can tell life, memories and sentences of the people imprisoned there. A discreet lighting instills to the museum and to its art gallery a mysterious atmosphere: hither and thither it casts surprising lighted layouts that bring out the beauty of paintings and frescos. The 150 masterpieces of the School of Art of Fiemme (made by Michelangelo, Cristoforo and Francesco Sebaldo Unterperger) hung on the walls showing their renewed charm. Some canvas are so well-lighted to let the visitor penetrate the space and approach the subject, as if they would tell him something secret.

In the prisons, the visitors can grab their torch to better watch the writings carved by the prisoners – actions, thoughts, memories. For instance, a cooper finely reproduced his tools on the wall. Another prisoner captured the image of his family house, another one proudly dreamt of stabbing someone else’s chest.

In the prisons, the visitors can grab their torch to better watch the writings carved by the prisoners – actions, thoughts, memories. For instance, a cooper finely reproduced his tools on the wall. Another prisoner captured the image of his family house, another one proudly dreamt of stabbing someone else’s chest.

In the Sixteenth century, these jail cells were savage prisons too, where the so-called witches of Cavalese were jailed. Down there are guarded, with great respect, the signs that had dictated the passing of a very dark and far time.

By exploring the rooms of the palace and going up and down the stairs, the visitor can experience the most important historical pages of Val di Fiemme. The guides reveal the ambitious of the prince-bishops and of the artists of the School of art of Fiemme, the theatrical visits embellish ancient habits, love stories, prisoner’s life and ancient gossip. Costume shows lead the public into the rooms of the prince-bishop’s summer housing. A suggestive and dated atmosphere is the companion of a brilliant and stimulating journey back in time, the direction is by Alessandro Arici of the company La Pastière.

Written by Beatrice Calamari APT of Cavalese

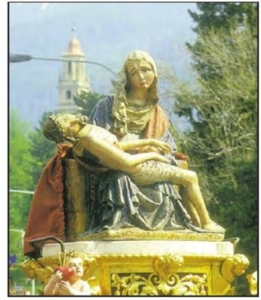

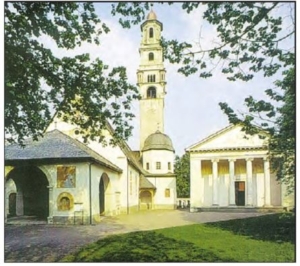

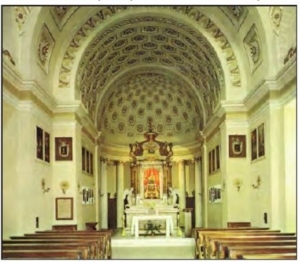

Madonna of the Val di Fiemme

The sanctuary of the Addolorata (The “Mother of Sorrows” or Pietà) is a cemetery chapel. The present-day chapel was built in 1829, designed by Giuseppe Dalbosco, who also designed the cemetery of Trento. It mirrors the architectural lines of Rome’s Pantheon. Previously, at this site,stood the chapel of the Bertelli family of Preore, which was indeed, used for funeral rites. The chapel had a crypt which, for some time, served as an ossuary, and an upper nave dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel. The legend concerning the founding of the chapel is similar to the one surrounding the development of the nearby chapel of Pierabla-Weissenstein. The state of the Pietà had been removed from the parish church in the sixteenth century when a new chapel, the Rosary chapel, was added. The statue could not be burned, as was the custom for wooden statues removed from churches and no longer needed. Instead, the statue was buried in sacred ground in the same parish cemetery. Discovered by accident in 1645, by the sacristan Vitale de Vitali, it was placed on the altar of the ossuary crypt of the Bertelli chapel, dedicated to St. Michael. Devotion for the sacred statue became widespread, the site became known as the Chapel of the Mother of Sorrows, becoming

The sanctuary of the Addolorata (The “Mother of Sorrows” or Pietà) is a cemetery chapel. The present-day chapel was built in 1829, designed by Giuseppe Dalbosco, who also designed the cemetery of Trento. It mirrors the architectural lines of Rome’s Pantheon. Previously, at this site,stood the chapel of the Bertelli family of Preore, which was indeed, used for funeral rites. The chapel had a crypt which, for some time, served as an ossuary, and an upper nave dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel. The legend concerning the founding of the chapel is similar to the one surrounding the development of the nearby chapel of Pierabla-Weissenstein. The state of the Pietà had been removed from the parish church in the sixteenth century when a new chapel, the Rosary chapel, was added. The statue could not be burned, as was the custom for wooden statues removed from churches and no longer needed. Instead, the statue was buried in sacred ground in the same parish cemetery. Discovered by accident in 1645, by the sacristan Vitale de Vitali, it was placed on the altar of the ossuary crypt of the Bertelli chapel, dedicated to St. Michael. Devotion for the sacred statue became widespread, the site became known as the Chapel of the Mother of Sorrows, becoming the destination of numerous pilgrimages. Finally, after a large bequest from Don Antonio Longo da Varena (who died in 1820), the old chapel was demolished and a new sanctuary was erected in its place and the statue has been there ever since. The first stone of the new sanctuary was laid in 1825 and it was consecrated on August 15, 1830 by Monsignor Giuseppe Riccabona, the bishop of Passavia. The statue of the Pietà has been taken from the sanctuary dozens of times,and carried in procession through the streets of the village. This has always happened in times of drought, plague, or other public calamities. For example, on July 2, 1782, the Community Council of Fiemme declared a solemn vow to the Pietà. Fifteen years later, in 1797, the people of Fiemme — and particularly, those of Cavalese- maintained they had been spared looting by the French armies, thanks to the protection of the Pietà. During the popular uprising of Andreas Hofer, the Community, fearing rioting, vote to ‘raise’ the statue. In the seventeenth century, there were numerous processions to exorcise the drought which threatened crops and therefore the very lives of the people. More processions took place in 1832, 1839, 1849, 1861 and 1881.

the destination of numerous pilgrimages. Finally, after a large bequest from Don Antonio Longo da Varena (who died in 1820), the old chapel was demolished and a new sanctuary was erected in its place and the statue has been there ever since. The first stone of the new sanctuary was laid in 1825 and it was consecrated on August 15, 1830 by Monsignor Giuseppe Riccabona, the bishop of Passavia. The statue of the Pietà has been taken from the sanctuary dozens of times,and carried in procession through the streets of the village. This has always happened in times of drought, plague, or other public calamities. For example, on July 2, 1782, the Community Council of Fiemme declared a solemn vow to the Pietà. Fifteen years later, in 1797, the people of Fiemme — and particularly, those of Cavalese- maintained they had been spared looting by the French armies, thanks to the protection of the Pietà. During the popular uprising of Andreas Hofer, the Community, fearing rioting, vote to ‘raise’ the statue. In the seventeenth century, there were numerous processions to exorcise the drought which threatened crops and therefore the very lives of the people. More processions took place in 1832, 1839, 1849, 1861 and 1881.

Sole men rites were celebrated during the two cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century. In 1836, the people of Fiemme turned to Maria with public prayers and on August 19th, there was a solemn procession with the miraculous statue. The scourge was avoided and not a single case of cholera was noted in Fiemme. In August of 1881, the town council of Fiemme again urged vows and prayers and even declared a fast of public penitence, imploring rain. Crowds of people flowed in, not only from every part of the valley, but also from the Adige Valley, from Egna, Montagna, Bronzolo and Val di Dembra. On August 2, 1881, 15,000 pilgrims were reported. The following year, on September 17, 1882, the Fiemme Valley, along with a large part of the Trentino, was devastated by catastrophic flooding. A votive tablet, hanging on the walls of the sanctuary, commemorates that event. It records that Pietro Ballante was saved after spending three days in the flood waters. And then the drought returned.

men rites were celebrated during the two cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century. In 1836, the people of Fiemme turned to Maria with public prayers and on August 19th, there was a solemn procession with the miraculous statue. The scourge was avoided and not a single case of cholera was noted in Fiemme. In August of 1881, the town council of Fiemme again urged vows and prayers and even declared a fast of public penitence, imploring rain. Crowds of people flowed in, not only from every part of the valley, but also from the Adige Valley, from Egna, Montagna, Bronzolo and Val di Dembra. On August 2, 1881, 15,000 pilgrims were reported. The following year, on September 17, 1882, the Fiemme Valley, along with a large part of the Trentino, was devastated by catastrophic flooding. A votive tablet, hanging on the walls of the sanctuary, commemorates that event. It records that Pietro Ballante was saved after spending three days in the flood waters. And then the drought returned.  Those were difficult years marked by hardships and seasonal migrations. Then came the First World War! At the end of that painful period, in 1919, the community leaders decreed that there would be an annual procession. In June of 1944, a new solemn vow was pronounced: “If the Valley would be spared the horrors of this war,” a special Mass would be celebrated every five years on the third Sunday of September. An ‘Act of submission to the Madonna Addolorata’ was declared on May 26, 1996. From promise to promise, from one vow to the next, especially in bad times, this sanctuary has been, for the people of the Fiemme, a source of hope, and if not hope, at least resignation.

Those were difficult years marked by hardships and seasonal migrations. Then came the First World War! At the end of that painful period, in 1919, the community leaders decreed that there would be an annual procession. In June of 1944, a new solemn vow was pronounced: “If the Valley would be spared the horrors of this war,” a special Mass would be celebrated every five years on the third Sunday of September. An ‘Act of submission to the Madonna Addolorata’ was declared on May 26, 1996. From promise to promise, from one vow to the next, especially in bad times, this sanctuary has been, for the people of the Fiemme, a source of hope, and if not hope, at least resignation.

In 1978, thieves sought to rob the statue, thinking it a praiseworthy wooden sculpture. But they had not figured its weight, it being an amalgam of alabaster and plaster of Paris. The Statue was dropped to the ground. It was subsequently sent to Bologna for restoration under the auspices of the Province of Trento. On May 24,1980, the statue was returned to the Fiemme community.