The Way They Were…

A common, popular and even daily activity in the villages of the Trentino was the Filó. It is pronounced fee ló with the accent on the last syllable. The expression for Filó…literally meant let’s do Filo or let us gather. The Filo` was a daily gathering of the villagers after their evening supper in the stables that were situated in their very homes. The stables being in their interior of the houses were insulated and further warmed by the body heat of their all important cattle that not only provided them with dairy products but served to draw their carts and till their fields. It was a welcomed conclusion of the day.

A common, popular and even daily activity in the villages of the Trentino was the Filó. It is pronounced fee ló with the accent on the last syllable. The expression for Filó…literally meant let’s do Filo or let us gather. The Filo` was a daily gathering of the villagers after their evening supper in the stables that were situated in their very homes. The stables being in their interior of the houses were insulated and further warmed by the body heat of their all important cattle that not only provided them with dairy products but served to draw their carts and till their fields. It was a welcomed conclusion of the day.

The adults engaged in their ciacerar, the chatter about the activities of the villages and their struggles as they pursued their farming to survive. Stories would be told. Often there would be a designated story teller who entertained the children as well as the adults with wonderful and engaging yarns. The stories relayed history, memories, as well as the morals and the expectations of the village community.

There were poems and sayings that expressed their sagezza and peasant wisdom. Songs would be sung. The songs were of the mountains, the young lovers, the wars, and their struggle. They sang often with the formula of Due Trentini, one choir. The women knitted, shucked corn and multi-tasked their chores while enjoying the company. The children played and the men would play cards or mora…a game with a great deal of gesticulating. Finally the Filó would conclude with the corona, the rosary in which they remembered their dead, their sick, and their relatives traveling through Europe working or emigrants to far off lands. There was a commonality in that all had the same limited means and the Filó was an engine of socialization.

Glimpses Into Our Past…

Just above Trento (17 km north of Trento), there is a village named San Michele all`Adige. It happens to be the place where Pinot Grigio Santa Margarita originates, one of the most popular wines in the USA. San Michele has the Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina, the Museum of the Customs and Costumes of the Trentino People. It is a museum that

Just above Trento (17 km north of Trento), there is a village named San Michele all`Adige. It happens to be the place where Pinot Grigio Santa Margarita originates, one of the most popular wines in the USA. San Michele has the Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina, the Museum of the Customs and Costumes of the Trentino People. It is a museum that has a history and is full of history, the history of our people. The building that houses this wonderful museum was once one of the many fortresses and palaces of the Counts of the Tyrol. The Trentino was the Tyrol both under the feudal bishoprics of Trento and Bressanone as well as under the Austrian Hungarian Empire and there were these Counts that served as the military arm of the bishoprics and protectors of their individual areas. The museum’s building became an Augustinian monastery and then the site of the remnants and artifacts of our ancestors, covering every aspect of the traditional culture of Trentino: agriculture, arts and crafts, folklore. The Museum was founded in 1968 by Giuseppe

has a history and is full of history, the history of our people. The building that houses this wonderful museum was once one of the many fortresses and palaces of the Counts of the Tyrol. The Trentino was the Tyrol both under the feudal bishoprics of Trento and Bressanone as well as under the Austrian Hungarian Empire and there were these Counts that served as the military arm of the bishoprics and protectors of their individual areas. The museum’s building became an Augustinian monastery and then the site of the remnants and artifacts of our ancestors, covering every aspect of the traditional culture of Trentino: agriculture, arts and crafts, folklore. The Museum was founded in 1968 by Giuseppe

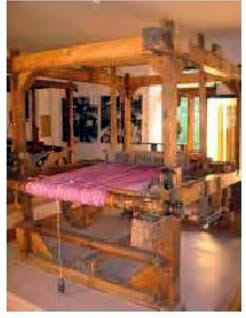

“Bepo” Sebesta, ethnographer, essayist, personality eclectic, considered father of the modern museography. The Museum at Santo Michele is the greatest regional Italian museum of folk traditions. The museum is the ideal place to discover memories and traditions of the valleys of Trentino. In its many rooms, there are displayed so many of the objects that created and enhanced the culture and life style of the area. There are the objects and practices, tools in all its shapes and styles, the use of animals. The use of the mulino, the water mill that powered the grain mills, the blacksmith, iron foundry. The kitchen with its artifacts and products. The production of the cheeses, grappa, bread, the cultivation of bees, vines and so many of the food stuffs that our emigrants remembered and attempted to replicate as they settled in the states. There are displays of the Filò, the wardrobes of the men and women, their religious practices, dialect and music.

“Bepo” Sebesta, ethnographer, essayist, personality eclectic, considered father of the modern museography. The Museum at Santo Michele is the greatest regional Italian museum of folk traditions. The museum is the ideal place to discover memories and traditions of the valleys of Trentino. In its many rooms, there are displayed so many of the objects that created and enhanced the culture and life style of the area. There are the objects and practices, tools in all its shapes and styles, the use of animals. The use of the mulino, the water mill that powered the grain mills, the blacksmith, iron foundry. The kitchen with its artifacts and products. The production of the cheeses, grappa, bread, the cultivation of bees, vines and so many of the food stuffs that our emigrants remembered and attempted to replicate as they settled in the states. There are displays of the Filò, the wardrobes of the men and women, their religious practices, dialect and music.

The Museo will become a collaborator in subsequent issues of the Filò and will attempt to explain and illustrate the customs and activities of our people covers every aspect of the traditional culture of Trentino: agriculture, arts and crafts, folklore. The website of the Museum is www.museosanmichele.it

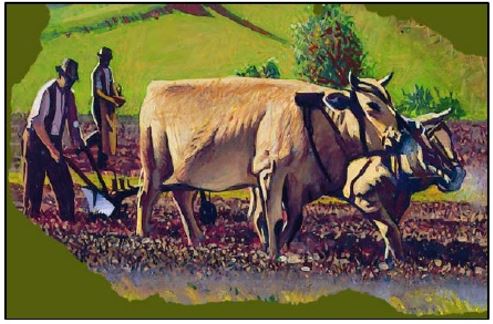

Il Contadin….The Farmer

The way of life of our ancestors was none other than to live and function as a contadino… More than a way of work , it was indeed a way of life, a total involvement with his lands, crops, animals and community to secure his survival and that of his family. To understand this interplay, one needs to understand the lands. The Trentino is 70% above 3,280 feet, 21.5 % between 1640 feet and 3280 feet and only 8.5% is under 1640 feet and sea level. The major part of the productive surface is encumbered by woods and pastures that belong collectively to the individual towns. What remains of arable land was divided into small plots of the individual contadini.

The way of life of our ancestors was none other than to live and function as a contadino… More than a way of work , it was indeed a way of life, a total involvement with his lands, crops, animals and community to secure his survival and that of his family. To understand this interplay, one needs to understand the lands. The Trentino is 70% above 3,280 feet, 21.5 % between 1640 feet and 3280 feet and only 8.5% is under 1640 feet and sea level. The major part of the productive surface is encumbered by woods and pastures that belong collectively to the individual towns. What remains of arable land was divided into small plots of the individual contadini.

their live stock. The smaller plots closer to the villages were dedicated to haymaking as well as wheat, corn, barley, rye, buckwheat, oats, and potatoes. There were family gardens that produced legumes and other vegetables as well as grape vines and for some families mulberry bushes to produce silk. To cultivate the grains, the lands needed to be plowed and the plow would be drawn by oxen or their cows or horses or a mule. The fields were planted and fertilized with manure of their livestock. When mature the various grains were cut with a hand sickle, gathered into sheaves and then beaten by hand to separate the grain from the chaff. The corn were woven into clusters and placed under the eaves of their houses or in their “attics” or “ere” since their houses combined their domicile with a functioning barn. They were placed there to be stripped at a later time. With grains separated, they brought them to the mulino, the miller, who used water driven wheels that had been in use in Tyrol since 800. These water wheels drove the grinding stones transforming the wheat into flour while the barley was striped of its core to make barley for orzetto or for minestrone or roasted to make a barley coffee. The array of the tools of the contadino are on display at the Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina at the village of San Micheleall`Adige. Their website is

their live stock. The smaller plots closer to the villages were dedicated to haymaking as well as wheat, corn, barley, rye, buckwheat, oats, and potatoes. There were family gardens that produced legumes and other vegetables as well as grape vines and for some families mulberry bushes to produce silk. To cultivate the grains, the lands needed to be plowed and the plow would be drawn by oxen or their cows or horses or a mule. The fields were planted and fertilized with manure of their livestock. When mature the various grains were cut with a hand sickle, gathered into sheaves and then beaten by hand to separate the grain from the chaff. The corn were woven into clusters and placed under the eaves of their houses or in their “attics” or “ere” since their houses combined their domicile with a functioning barn. They were placed there to be stripped at a later time. With grains separated, they brought them to the mulino, the miller, who used water driven wheels that had been in use in Tyrol since 800. These water wheels drove the grinding stones transforming the wheat into flour while the barley was striped of its core to make barley for orzetto or for minestrone or roasted to make a barley coffee. The array of the tools of the contadino are on display at the Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina at the village of San Micheleall`Adige. Their website is

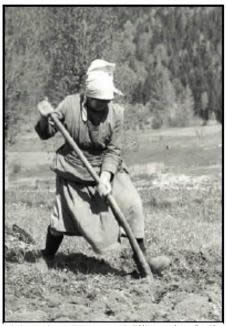

Women in Alpine Agriculture

Alpine women, especially those areas where there had occurred a great deal of emigration by men, engaged in the multi-faceted job of Alpine farming. Younger women tended cows and oxen as well as the flocks of sheep and goats while the older women cultivated the fields and crops, processing the sequences of chores to create and store hay for their animals without their neglecting their household tasks and families. This gave women more autonomy and independence in agriculture, previously carried out by men. In the Trentino, the emigration of the males was widespread. At first, seasonal migration to the Po Plain south then the migration spread to Central Europe. Finally, as conditions demanded, the males began their emigration from the Trentino to North and South America. Due to the wartime draft, womenfolk had assumed not only the ordinary tasks but traditional male tasks.

Alpine women, especially those areas where there had occurred a great deal of emigration by men, engaged in the multi-faceted job of Alpine farming. Younger women tended cows and oxen as well as the flocks of sheep and goats while the older women cultivated the fields and crops, processing the sequences of chores to create and store hay for their animals without their neglecting their household tasks and families. This gave women more autonomy and independence in agriculture, previously carried out by men. In the Trentino, the emigration of the males was widespread. At first, seasonal migration to the Po Plain south then the migration spread to Central Europe. Finally, as conditions demanded, the males began their emigration from the Trentino to North and South America. Due to the wartime draft, womenfolk had assumed not only the ordinary tasks but traditional male tasks.

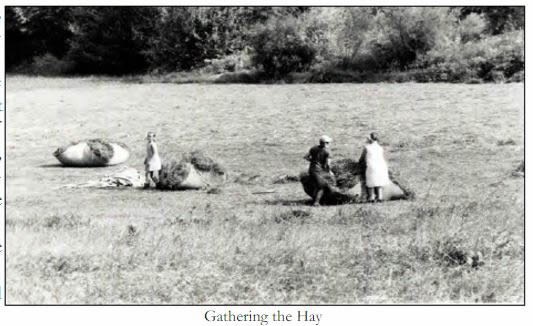

In reality, even when the men were present, the women were always quite busy. They bore many heavy loads on their shoulders and their heads or in the gerla, a basket attached to their backs. The gerla was their companion even as little girls, the balancing rod to carry pails of water from the fontane, the one and only source of water in the village. On their backs, they carried large hay nets down from the fields to the haylofts above their homes. Their tasks and obligations away from the hearth of the home were many and varied: they sowed seeds, attended to fertilizing the fields, they harvested crops, milked the cows and goats, attended to their vegetable garden, they shucked corn, harvested the crops, took care of the stables refreshing the farlet, the bed of hay and leaves for the animals, fed the animals, grew flax seed and hemp and performing all the successive tasks to render the canepa into twine to make chairs. All these were the tasks and the functions of the women. Most of the haymaking process was exclusively the skills of the women. After the men cut the grass, the wives, mothers-in-law and daughters as well as the younger children of the family spread the grasses to dry them, turning them over several times before stacking it for the evening. Hence, the many steps of the haymaking involved the gathering of the hay,its rotation, gathering it in large nets (see illustration), bringing it in from the fields and arranging it in their haylofts situated on the Upper levels of their homes. All these difficult and time consuming tasks were the work of the women of the household. In the Trentino, in particular the Vallagrina, there was a specific and exclusive function of the women: the cultivation of mulberry trees and silkworms which was usually inside the homes of these“women farmers.” The difficult and demanding work involved the selection of the seed and the incubation and rearing of the silkworms.

turning them over several times before stacking it for the evening. Hence, the many steps of the haymaking involved the gathering of the hay,its rotation, gathering it in large nets (see illustration), bringing it in from the fields and arranging it in their haylofts situated on the Upper levels of their homes. All these difficult and time consuming tasks were the work of the women of the household. In the Trentino, in particular the Vallagrina, there was a specific and exclusive function of the women: the cultivation of mulberry trees and silkworms which was usually inside the homes of these“women farmers.” The difficult and demanding work involved the selection of the seed and the incubation and rearing of the silkworms.

Obviously, these functions were integrated into in all that was entailed in their domestic economy and household management…the daily tasks and the feeding of their families, educating children in manners and religious education. A task particularly assigned to the women. Women were seen as the guardian of family traditions. Her activities were fundamental to the social relationships of the family and the transmission of the ethical and cultural values across generations. This was the “female role and function” in the Alps: a love for the work and the family, sacrifice and physical fatigue of the tireless Alpine woman.

Daniela Finardi – Daniela Finardi, Communications Dept -Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina

Trentino Woman Tilling the SoilGathering the Hay

Le Rogazioni…The Petitions

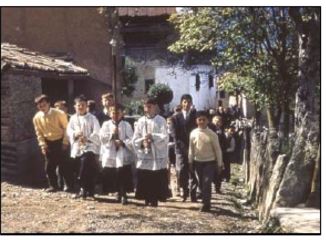

Springtime…nature and love awaken! From ancient times, there occurred the rites of spring, the seeding and the planting of the fields followed by the invocations and petitions to God to bless them, the farmers, his animals, and his fields. In the Tyrol, from Palm Sunday to Pentecost, there would be le Rogazioni or litanies or petitions carried out in liturgical splendor with processions, vestments, processional crosses. They were usually three days in duration. There were the Major Rogations and the Minor Rogations. Every family contributed minimally one member to participate in these processions that proceeded through their immediate territory with invocations against pestilence, storms, hail and whatever else impacted on their agriculture while at the same time there were invocations for abundant harvests. The prayers were said and sung in a choral manner alternating the petitions with responses. “From pestilence …deliver us, O Lord.” At the conclusion of the procession and the visitation of the fields, the priest would impart a final blessing…“ai quattro angoli della terra”…to the four corners of the earth. Bells were frequently run not just for the liturgical activities but also to ward off the demonic spirits.

Springtime…nature and love awaken! From ancient times, there occurred the rites of spring, the seeding and the planting of the fields followed by the invocations and petitions to God to bless them, the farmers, his animals, and his fields. In the Tyrol, from Palm Sunday to Pentecost, there would be le Rogazioni or litanies or petitions carried out in liturgical splendor with processions, vestments, processional crosses. They were usually three days in duration. There were the Major Rogations and the Minor Rogations. Every family contributed minimally one member to participate in these processions that proceeded through their immediate territory with invocations against pestilence, storms, hail and whatever else impacted on their agriculture while at the same time there were invocations for abundant harvests. The prayers were said and sung in a choral manner alternating the petitions with responses. “From pestilence …deliver us, O Lord.” At the conclusion of the procession and the visitation of the fields, the priest would impart a final blessing…“ai quattro angoli della terra”…to the four corners of the earth. Bells were frequently run not just for the liturgical activities but also to ward off the demonic spirits.

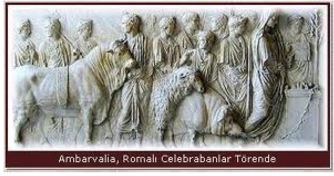

These rituals as so many others had their roots in pre-Christian times. St Virgilius began the evangelization in the IV Century and the transition to Christianity proceeded slowly for centuries. Bishop Virgilius had sent several missionaries to the Val di Non where they were martyred by Anauniesi farmers since they had disturbed and interrupted their spring rite of Ambarvalia. This ancient Roman rite was conducted to honor the Roman deities of Mars, and Saturn, the deity of Agriculture for the purpose of preserving their fields form harmful things and to achieve an abundant harvest. These ambarvali rites were conducted three times proceeding reciting “litanies” through the fields leading a sow, a sheep and a bull. These animals were then sacrificed to deities to purify themselves and bless their agriculture. Christianity simply transformed these rites into their liturgies. Just before the millennium, in the Trentino, these rites became days of fasting and expiation with penitential and propiatory processions to petition God to enhance the fertility of the fields and their animals and their homes.

These rituals as so many others had their roots in pre-Christian times. St Virgilius began the evangelization in the IV Century and the transition to Christianity proceeded slowly for centuries. Bishop Virgilius had sent several missionaries to the Val di Non where they were martyred by Anauniesi farmers since they had disturbed and interrupted their spring rite of Ambarvalia. This ancient Roman rite was conducted to honor the Roman deities of Mars, and Saturn, the deity of Agriculture for the purpose of preserving their fields form harmful things and to achieve an abundant harvest. These ambarvali rites were conducted three times proceeding reciting “litanies” through the fields leading a sow, a sheep and a bull. These animals were then sacrificed to deities to purify themselves and bless their agriculture. Christianity simply transformed these rites into their liturgies. Just before the millennium, in the Trentino, these rites became days of fasting and expiation with penitential and propiatory processions to petition God to enhance the fertility of the fields and their animals and their homes.

At the dawn of 19th century in the Trentino, crosses of stone or wood were placed on the mountain peaks, in the fields as votive offering to avoid pestilence,  diseases to to their animals and the memory of calamities and natural disasters. They were also erected to mark Jubilees that were celebrated by the Church. In some areas the acolyte placed a wooden cross to mark the passage of procession. In the Bleggio, with its Pieve church, the Church of the Holy Cross, every home had a cross on their front door. Keep in mind that houses in the Tyrol combined their domiciles with their barns.

diseases to to their animals and the memory of calamities and natural disasters. They were also erected to mark Jubilees that were celebrated by the Church. In some areas the acolyte placed a wooden cross to mark the passage of procession. In the Bleggio, with its Pieve church, the Church of the Holy Cross, every home had a cross on their front door. Keep in mind that houses in the Tyrol combined their domiciles with their barns.

After the Council of Trent, these practices were modified to control some of the abuses of the merrymaking consistent with the many ancient fertility festivities. Vatican Council II further modified the ancient practices while allowing them to go on. However, the new fertilizers and insecticides have become the real conclusion of these traditional agricultural/liturgical practices.

Alberto Folghereiter is a prolific writer who combines a profound scholarship with a passion for the Trentino, its culture, history and people in over 15 books, newspaper articles, radio and speaking engagements. His most recent book in English is “Beyond the Threshold of Time” – Available at Amazon. This article is drawn from “La terra dei Padri” Curcu & Genovese, Trento 1998.

The Carnivals . . .

Sti ani …long ago…and even now as folkloristic celebrations, the Tyrol staged celebratory carnivals that were associated both with Christian celebrations as well as seasonal celebrations that have their roots in pagan pasts.

Sti ani …long ago…and even now as folkloristic celebrations, the Tyrol staged celebratory carnivals that were associated both with Christian celebrations as well as seasonal celebrations that have their roots in pagan pasts.

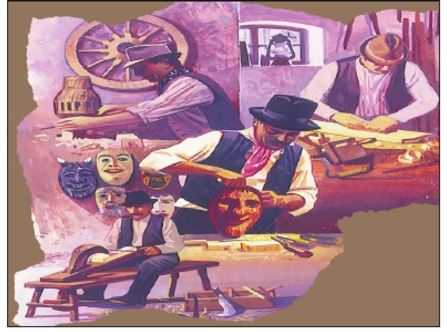

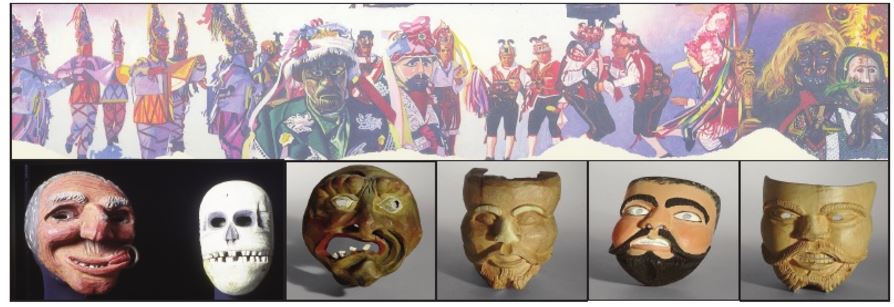

The word, “Carnevale,” means “so long meat” suggesting a vestibule for a period of abstinence…a Mardi Gras, a Fat Tuesday during which “the world is turned upside down” with an overabundance and indulgence with food and a freedom without rules. Reminiscent of these past customs, just prior to Lent, there are numerous and very different traditions associated with the Carnival. In the Valsugana, the evil Count Biagio is put on trial and sentenced (See Fall Filo` 2012). At Grauno and Romarzollo, there is focus on themes of woodland and forest perhaps simulating the importation of the woodland deities of the ancient Romans. In Val floriana and Valle di Fassathey wear painted wooden masks. In the Val di Mochenithe rites celebrate the passage from adolescence to adult-hood while in other valleys; there are itinerant troupes of dancers performing in village squares. The first of these celebrations replete with colorful masks occur in January on the feast of St. Antony the Abbot, patron of the animals and is repeated several times until Shrove Tuesday.

The two principal masks of many carnivals are Bufonand Lachè who pass from house to house announcing the celebrations. The Bufon has already abandoned himself to buffoonery and heralds the dance of the Lachèthe big masks. Other times there is a procession with a variety of masks and characters: comic figures, i belli (the good looking), i brutti (the ugly), i vecchi (the old), the wild men and other frightening figures.

The notable carnival of the Valfloriana of the Val di Fiemme is itinerant and passes through all 13 sections of the commune from early morning to the evening. The different figures appear one by one… The first to arrive are the matoci with their typical wooden masks, totally disguised, carrying a bell, uttering imprecations. The villagers seek to stop them and engage them in a cross examination regarding their identity and place of origin. There follows the sonadori (musicians) followed by arlechini , the harlequins, clowns with high cone shaped hats dancing to the music of the accordions of the sonadori. They are followed by a procession of sposi, spouses, and finally paiaci, clowns who do a mime. This diverse procession goes from hamlet to hamlet, enjoying vin brule, mulled wine in each place.

The masks below can be found at the Museum of Ways and Customs of the Trentino People.

Stufe … Stoves of the Val di Non

The Tyrol, now the Trentino, occupies the border between the mid-European area, known for its amazing majolica (maiolica) stoves, and the southern lands, which use none at all and simply utilize the open fire. The tile stove is designed to conserve heat and maximize the radiation in an environment. These stoves are called in Italian stufe a olle (– òleare decorated majolica tiles used to construct the stove.

The Tyrol, now the Trentino, occupies the border between the mid-European area, known for its amazing majolica (maiolica) stoves, and the southern lands, which use none at all and simply utilize the open fire. The tile stove is designed to conserve heat and maximize the radiation in an environment. These stoves are called in Italian stufe a olle (– òleare decorated majolica tiles used to construct the stove.

These stoves began their spread in the Trentino in the 15th and 16th centuries, and employ a complex interior structure of ducts that trap heat inside, thereby using wood is more efficiently. The chimney is completely hid-den in the wall next to where the stove is built. The hole is placed at the bottom so that the fumes are forced to a reverse turn. The loading of the stove, for convenience and cleanliness, is always made from a mouth open to a hallway or kitchen. The òle, baked clay, are glazed and have different shapes, often with relief decoration. The shape and the decoration of the panels with which they are constructed make the stove important element of furniture. Some deposits of pure clay for the construction of stoves had been discovered, specifically in the Val di Non,  particularly in the area of Sfruz, Sfruz, one of the oldest and highest located localities of the Val di Non valley. The name Sfruz comes from forare (to drill). Proximate to the village were the areas where there was extracted clay of lake origin of excellent quality. They were called Credai and Sette Larici.

particularly in the area of Sfruz, Sfruz, one of the oldest and highest located localities of the Val di Non valley. The name Sfruz comes from forare (to drill). Proximate to the village were the areas where there was extracted clay of lake origin of excellent quality. They were called Credai and Sette Larici.

In the sixteenth century, there occurred a emigration of skilled workers of Protestant faith from Faenza who further developed and refined the skill. In 1800, many work-shops were active and engaged in working the clay to create not only stoves, but also pottery, bricks, tiles and pipes. The eighteenth-century stoves are mostly white with painted decorations with floral motifs in blue or green. There followed other styles with monochromatic colors: white, green, brown, with floral or geometric relief decoration in white. The Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina located in St Michele alla Adige, a town just above Trento, has a collection of fifteen complete tile stoves of different periods and styles.

The Museum contains the most “aristocratic” models that have a tower-like form. This extended heightened form enhanced the height of the combustion chamber increasing the radiating surface. This type of stove is very often in the castles of the Val di Non. The museum also displays other examples found in more common settings, designed in the form of a box (a muletto). A wooden frame sometimes constructed around the stove functioned as a warm place to sit. Often on the top lunette is marked the date of construction.

Written by Daniela Finardi, Museo degli Usi eCostumi della Gente Trentina

Barca di San Pero: St. Peter’s Boat

Our people were deeply religious and they incorporated their religiosity in their daily lives and work. The rhythm of the year fol-lowed the rhythm of the liturgy and the church and local celebrations. One such celebration or religious custom was “la barca di San Pero”….St. Peter’s boat. In June, the Church celebrates the Solemnity of St. Peter and Paul. Our people were neither great theologians nor biblical scholars, but simple, yet religious people who had creative ways of inserting or using ordinary ways to express extraordinary things. Permit me to insert myself into this narrative…

Our people were deeply religious and they incorporated their religiosity in their daily lives and work. The rhythm of the year fol-lowed the rhythm of the liturgy and the church and local celebrations. One such celebration or religious custom was “la barca di San Pero”….St. Peter’s boat. In June, the Church celebrates the Solemnity of St. Peter and Paul. Our people were neither great theologians nor biblical scholars, but simple, yet religious people who had creative ways of inserting or using ordinary ways to express extraordinary things. Permit me to insert myself into this narrative…

It was June 1948; I was almost 7 years old and was in Cavaione in the Bleggio of the Val delle Giudicarie visiting with my mom and sister my nonni and family. It was June 28th.Nona Teresa and Zia Angelina said…Louis…femte la barca de San Pero? Let’s make St.Peter’s boat. They proceeded “a far filo`”…they did afilo`…they gathered me…at the kitchen table and explained how St Peter and St Paul had missionary journeys to their churches scattered everywhere and traveled by foot and by boat. (They could not have been more biblically literate since they simply recounted the narratives found in the Acts of the Apostles)… Here is what we did..

Nona broke an egg and removed the yolk. She got a large jar and placed a liter of water in it…we placed the egg white into the bottle and placed it into the water and the non the window sill between “la finestra e I scuri” between the window and the shutters. I have a memory of being a bit of the New York skeptic not exactly sure what was to happen…I went to bed and got up as if it were Christmas morning and…Yes! There it was…St. Peter’s boat…whatever might have been the mystical forces or simply the chemistry and the cold night air of the mountains…but there it was…a form of a ship. St.Peter’s ship. Wow!

There followed a profound discussion among I veci…the elders as to what the next couple of months of weather might bring. If the “ship” or its figure was enlarged, the prognostication was that there would be a hot and dry summer. If, instead, the “sails” seemed flat more like a life raft of a shipwreck…the weather that summer would be “shipwrecked.” I learned indeed about St. Peter but I think I learned or sensed the wisdom of these mountain peasants that read the signs of times in all that surrounded them.

There followed a profound discussion among I veci…the elders as to what the next couple of months of weather might bring. If the “ship” or its figure was enlarged, the prognostication was that there would be a hot and dry summer. If, instead, the “sails” seemed flat more like a life raft of a shipwreck…the weather that summer would be “shipwrecked.” I learned indeed about St. Peter but I think I learned or sensed the wisdom of these mountain peasants that read the signs of times in all that surrounded them.

I need to thank Alberto Folgheraiter, the brilliant and prolific raconteur of the ways and customs of our people. At lunch in a villa overlooking the city of Trento, herein forced my memory and explained how it was a custom in all the villages of the Trentino. In his book La Terra dei Padri. Storie di gente e di paesi, he presents the custom and the illustrations of this article. This story is true…and in the words of Alberto…it is Storie minimedi quei chi non ha storia…Small stories of those who do not have history…but, Alberto, they do…in the Filo`. Thanks

PS: The picture below is the doorway of the kitchen where we had prepared the “barca” and the window is where we placed the jar…it is also the doorway of my kitchen of my house where I return twice a year. (I made the bench…)

Fiemme’s Treasure: Its Woods

Imagine…to this day, the city of Venice still lies on the trunks of spruces and larches of Val di Fiemme. After consuming the woods in the flat-lands, Venice started to import high-trunk trees from the Alps and the Dolomites, in particular from Valdi Fiemme, carried out along the streams of water. The very construction of the ancient city of Venice situated on water depended on the importation of huge amounts of wood to allow the civil engineering of its city: basement poles, attics, roofs, doors and windows, design, etc. The Valley’s forest provided the material or the Venetian shipyards to construct the ships that dominated the world for over 300 years.

Imagine…to this day, the city of Venice still lies on the trunks of spruces and larches of Val di Fiemme. After consuming the woods in the flat-lands, Venice started to import high-trunk trees from the Alps and the Dolomites, in particular from Valdi Fiemme, carried out along the streams of water. The very construction of the ancient city of Venice situated on water depended on the importation of huge amounts of wood to allow the civil engineering of its city: basement poles, attics, roofs, doors and windows, design, etc. The Valley’s forest provided the material or the Venetian shipyards to construct the ships that dominated the world for over 300 years.

But the forests of Val di Fiemme are famous worldwide for another reason. The famous Stradivari used to construct his renown violins with the wood of the spruces that grow in this Valley. There are very few European forests where this prestigious wood can grow and be used to create violins and other musical instruments. The Val di Fiemme is one of these magical valleys where you can see the whole production chain of this precious raw material. The wood is mainly produced by spruces grown in a unique context that combines exclusive land and climate. It has extraordinary mechanical-sounding features. The “resonance spruce” is still sought-after and used to create harmonic boards for string instruments such as organs, pianos, violins and others that are used and played in every corner of the world. It is studied and tested by many universities and research laboratories –In the world of music, people usually refer to the Val di Fiemme as the “Forest of the Violins” or “The Valley of Harmony.” There is a long tradition of constructing harmonic boards – deeply rooted in this valley. A valley enterprise, Ciresa of Tesero, has become the premier firm for the international manufacturers of musical instruments. It is estimated that throughout the world there are over 160,000 pianos being played manufactured with the wood of Fiemme. One area of the Val di Fiemme that best represents this special tradition if not a vocation is a forest high above the area of Predazzo.

“The Resounding Forest, il Bosco che Suona. The columns of this outdoor “temple of music” are red spruces. The distinctive red spruces, appreciated by Stradivari and other great master flute makers like the Guarnieris and the Amatis. Every summer, these forests embraces a unique musical ritual. Renown international musicians gather at a high altitude to take part in a music festival, “The Sound of the Dolomites.” The participating musicians are asked to choose their personal spruce as a gift of Val di Fiemme given to artists who diffuse sublime melodies throughout the world, playing instruments that originate from these very forests, welcoming and well-kept places, thanks to the thousand-year management of Magnifica Comunità di Fiemme.

Effectively, several spruces in this thick forest are already “branded” with the names of international musicians: Uto Ughi, Daniel Hope, Uri Caine, Ivry Gitlis, etc. Very often, the artist develops a curious affinity with his designated tree. The ritual ends when the artist plays a track dedicated to his spruce. A mysterious resonance between man and nature vibrates in the wood. Magically, this affinity becomes palpable between these two living beings of different species, but carrying some identical chromosomes.

It is a skill of the craft to recognize the “resonance” in a spruce and to discern whether the trunk has the proper characteristics for a good musical instrument and whether it has the potential for the sought after “sound.” Many master flute makers focus on the trunk to exclude possible knots from young branches that might impede the good vibration of the sound. The regular imprints that distinguish the resonance spruce can be recognized just by lifting a tiny portion of the bark. When the tree is felled, you can see these imprints in the top section.Furthermore, the master flute makers even deem the position of the spruce compared to the plants of its same age in the whole group, to understand whether it was subjected to the action of wind or if the young plants near it while growing might have depleted its“nourishing” and changed its growth and the regularity of its fibre, over the years. The best period to fell the tree down is in the late autumn, when the wood is dormant and stores less fluids and nourishment. Tradition suggest a waning moon to capture its best features. Quite a tradition! Quite a skill….quite a story!

Written by Beatrice Calamari

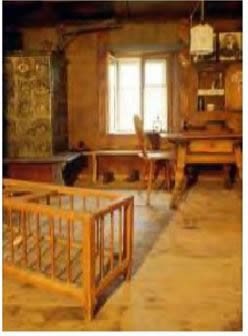

La Cuna: The Cradle

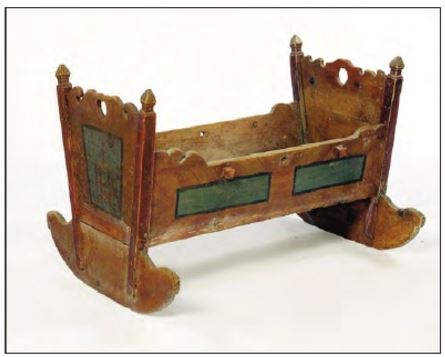

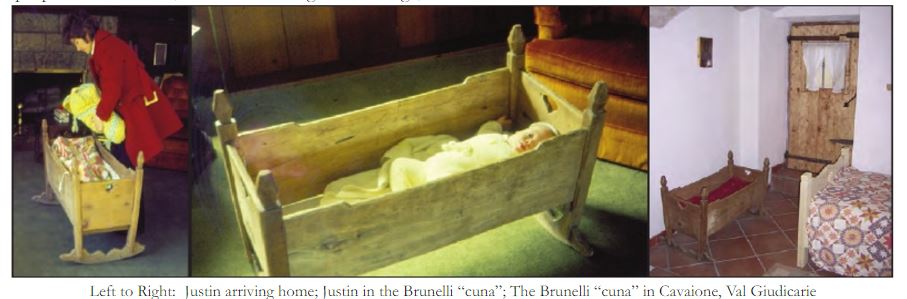

Our people began their lives in the tender embrace or cradle of their mother’s arms and breast and continued in the lovingly crafted cune…cradles passed from family to family. These cune in the Tyrol as well as most Alpine communities were crafted with a tradition of decorative carvings and inlay which reflected the strong religiosity and popular beliefs. Their shapes were very simple with sloping sides often carved or inlaid with decorative elements. Their posts shaped or milled with traditional columns with fluted or rounded shapes. On the head-board and end board there were holes often shaped as hearts that served as handles to move the cuna from the bedroom to the kitchen. The legs were attached to two curved pieces that served as the rocking elements. Often whether at table for a meal or seated to sew and mend clothes, the mother would use her foot to rock the cradle as she “multi-tasked.” Usually there was placed a round-ed band or frame on which there was placed a light piece of cloth to form a canopy to shield the infant from the light and from insects.

Our people began their lives in the tender embrace or cradle of their mother’s arms and breast and continued in the lovingly crafted cune…cradles passed from family to family. These cune in the Tyrol as well as most Alpine communities were crafted with a tradition of decorative carvings and inlay which reflected the strong religiosity and popular beliefs. Their shapes were very simple with sloping sides often carved or inlaid with decorative elements. Their posts shaped or milled with traditional columns with fluted or rounded shapes. On the head-board and end board there were holes often shaped as hearts that served as handles to move the cuna from the bedroom to the kitchen. The legs were attached to two curved pieces that served as the rocking elements. Often whether at table for a meal or seated to sew and mend clothes, the mother would use her foot to rock the cradle as she “multi-tasked.” Usually there was placed a round-ed band or frame on which there was placed a light piece of cloth to form a canopy to shield the infant from the light and from insects.

On the cradle sides and the canopy frame, there were hearts, geometric shapes, an array of flowers, e.g. edelweiss, as well as religious symbols which had a fundamental purpose of preserving the infant’s delicate life at times when there was a great incidence of infant mortality. The most common symbol was that of the……….IHS, the Greek words for Jesus Often too, there the monogram of M for the Virgin Mary followed by various Marian invocations. Another practice was to embroider the pillow with a prayer or lace a holy card under the pillow with some pious invocation. It was the occasion of the Winter Filo`s, those nightly gathering and in the stables and respites from their daily work where the shepherds and the contadini, the farmers, would commit themselves to the carving and decorating of their beloved cune.

On the cradle sides and the canopy frame, there were hearts, geometric shapes, an array of flowers, e.g. edelweiss, as well as religious symbols which had a fundamental purpose of preserving the infant’s delicate life at times when there was a great incidence of infant mortality. The most common symbol was that of the……….IHS, the Greek words for Jesus Often too, there the monogram of M for the Virgin Mary followed by various Marian invocations. Another practice was to embroider the pillow with a prayer or lace a holy card under the pillow with some pious invocation. It was the occasion of the Winter Filo`s, those nightly gathering and in the stables and respites from their daily work where the shepherds and the contadini, the farmers, would commit themselves to the carving and decorating of their beloved cune.

Written by Daniela Finardi, Museo dei Usi eCostumi della Gente Trentina.

Editor’s Note: The Odyssey of an Emigrant Cradle

In 1931, my mom Adele was expecting her first born, my brother Nino…Cesare in the Bleggio of the Valdelle Giudicarie. Zio Sandro exercised this Tyolean tradition and crafted a simple cuna that rocked and was replete with heart shaped handles and fluted columns. Nino was to use it for many months after which he was taken up by Mom to follow the pathway of the emigrant to join my dad in New York City. No longer of any use,it hung around in the era, the upper portions of the Tyrolean house, abandoned. But then came my cousins: Angelo, Luigi, Maria and Bruno…they all took their turns to be cradled in Zio Sandro’s cuna. After its happy years of service, it was again relegated to the era, the attic…abandoned and seemingly no longer of any or purpose. In the 1972, while vacationing in the village, I went up to very old ancestral house…to the stable, la stalla…now my bedroom..only to find my dad Agostino and my Zio Maso with hammers in their hands ready to knock it to pieces to make “na gabbia dei cunei”, a cage for rabbits. S T O P…I screamed, grasping it out of their hands…I lovingly dismantled it removing its wood-en pegs, packed it in my bags and it flew across the ocean to New York. Reassembled…ti received Justin as he was brought home from the hospital who then used for first several months of Justin’s infancy…this emigrant cuna then performed its services for Christian and Jeremy and Maria and Joseph. The emigrant Odyssey continued and possibly ended as I then packed it up and returned it to Cavaione, to the stable…my bedroom…honored and cherished and revered as the very symbol of the emigrant.

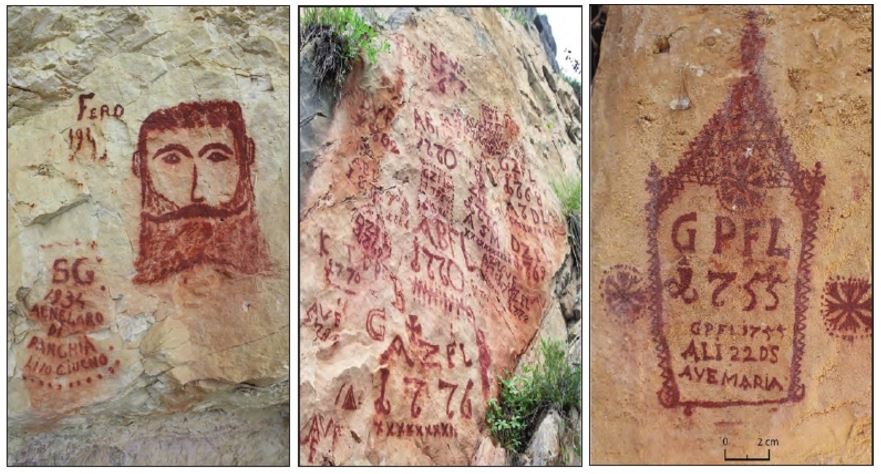

Inscriptions of the Shepherds

In the Trentino, the valleys of Fassa, Valsugana, Mochena, the valley of the Tesino, and especially the valley of Fiemme, were localities in which herding sheep and goats was a major occupation.

In the Trentino, the valleys of Fassa, Valsugana, Mochena, the valley of the Tesino, and especially the valley of Fiemme, were localities in which herding sheep and goats was a major occupation.

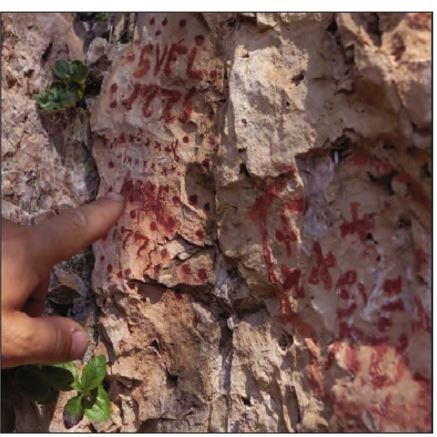

The mountains of Fiemme, in fact, were among the principal centers of sheep herding – especially on the massive Monte Cornon, the mountain which towers over the people of Tessero, Panchia`, Ziano di Fiemme and Predazzo. These pastures hosted shepherds and their flocks since prehistoric times. During their long stays among the pastures and the boulders, those shepherds chose to leave a trace of their presence, leaving us more than 30,000 inscriptions, made during the long hours of that lazy free time which was typical of their work day. The slopes of the Cormon are made up of rough terrain, suitable for grazing, and very steep white cliffs, whose calcareous composition was ideal for the red writing of the shepherds, almost as if they were giant outdoor chalkboards, upon which one could jot down one’s thoughts. The shepherds, during the summer months, spent long periods in the mountains without ever descending to the valley below. Their work, engaged in by the men in the area, was one of great solitude, and their cliff writing undoubtedly helped them while away the time. Their writing has been well preserved to this day, mainly because the area where they are found was virtually abandoned after 1950, when the sun set on the old pastoral system, the shepherd disappeared, and his subsistence economy gave way to the market economy.

The cliff writings were made with a ‘bol’ ( a dialectical word not readily translated into English). The bol was a shard of hematite, a mineral, reddish in color, which was easily found in several mines of the val di Fiemme, and in the val di Fassa. Among the mines was the one at

Ziano di Fiemme, called ‘Cava del bol’. The bol was used by the shepherds to mark the fleece of their sheep with a pattern of stripes. In order to have the color adhere to the rock permanently, the shepherds used a binder, a liquid chosen from water, sheep or goat’s milk, saliva or urine. They would put a few drops of the liquid on a flat rock, then rub the bol on the wet stone, producing a thick paste. In some cases, the bol was crushed and the resulting powder was mixed with the liquid. A specially prepared twig was used to do the actual writing. The twig was chewed at one end, softening the fiber until it resembled the bristles of a paintbrush. The color of the writings vary from a very intense red to paler shades, depending on the binder which was used. For example, a dark red resulted when goat’s milk was used, perhaps because of its high fat content. From a chronological point of view, the cliff writings have been dated as being written from the mid 1600’s until the first half of the twentieth century. The writings are all very much alike but there are some distinct differences, so that they fall into two groups. There were the writings made prior to 1850, i.e. from 1650 to about 1850, contain initials of the writer, some indication of their family, counts of their livestock and a few pictures or symbols, such as hunt scenes, drawings of animals, scenes of everyday life. Later inscriptions (from 1850 to 1950) include the full name of the writer, an indication of his home town, and frequently, messages regarding a certain event – either a public event or a milestone in the life of the writer. This occurrence of pastoral graffiti is seldom noted in the historical and cultural records of the Trentino. The inscriptions, however, are a witness to the existence of the shepherds in these localities and they are the means by which those shepherds chose to make known to us their identity and the importance of their work.

Written by Eleonora Dolzani,Museo Degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina